I recently finished writing a book on entrepreneurship in fashion. Before submitting it to my publisher, I had to go through a checklist to ensure that all was in order. One of the items on the list, was to remember to use images which reflect racial diversity. That’s when it struck me that in actual fact, this was not going to be as straightforward as I had expected. Historically, there has been a lack of diversity in the higher echelons of the industry, so such photos would be scarce.

In my book, I take a historical approach, in an attempt to understand the entrepreneurial capabilities of the fashion designers who shaped the industry, as we know it today. This journey begins in the 19th century, with the career of renowned English fashion entrepreneur, Charles Worth. But were there no influential fashion designers from ethnic minorities during that period? Today we recognize and celebrate renowned African-American designers such as Virgil Abloh, Stella Jean, Olivier Rousteng, Patrick Robinson and Telfar. But I was keen on the names that were forgotten or simply never given the recognition that they deserved, for their historical contribution to this colossally influential industry.

Photo credit: Jamie Stoker

Photo credit: Jamie Stoker

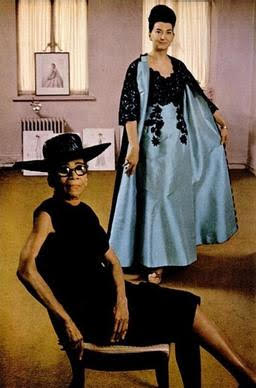

As it turns out, the first African-American designer became a designer almost by accident. Her name was Ann Lowe, born in Clayton, Alabama in 1898. She had acquired dressmaking skills from her mother. Ann lost her mother at the age of 16, inheriting an unfinished job, which had to be completed. This was the creation of four ballgowns for the First Lady of Alabama. It was the successful creation of these ballgowns, that launched her career path. Ann eventually moved to New York to study fashion design, enrolling in the S.T. Taylor Design School, that accepted her without realising they had admitted a woman of colour. Upon her arrival, they decided she would be segregated for the duration of her studies.

In 1950, Ann launched Ann Lowe’s Gowns in Harlem, becoming the go-to dress designer for the crème-de-la-crème of high society, with clients such as the Rockefellers, the Roosevelts, and the Du Ponts. She was called “society’s best kept secret.” She created the dress that Olivia de Havilland wore to accept her Oscar, but her name was not on the label, and she did not receive recognition for her work. Unfortunately, this wouldn’t be the last time that Ann failed to receive credit. In 1953, Ann scored a historical commission when she was hired to create the wedding dress of Jacqueline Bouvier (Jackie O). When asked, Jackie O simply said it was by “a colored designer”. The lack of recognition and acceptance, despite creating haute couture gowns, meant that she could charge very little, never allowing her to overcome her financial struggles. Her clients loved her low prices and kept returning for more, but Ann was just making ends meet.

Ann Lowe was just one of many African-American fashion entrepreneurs whose talent and contribution were kept quiet, only adding to the lack of diversity portrayed in the history of the fashion design industry.

While fashion draws inspiration from diverse cultures and backgrounds, the reality is that fashion is homogenous, not only when it comes to race, but also ethnicity. It is difficult to break into this industry, and I believe, given what history tells us, it is even more difficult for people from diverse backgrounds to achieve success. In my book, it is not until the 1970s that we see what I refer to as the “changing face of the fashion business”. It came with the emergence of Asian designers, and more particularly, Japanese designers such as Issey Miyake, Kenzo Takada, and Rei Kawakubo.

Photo credit: British Vogue

Photo credit: British Vogue

Fashion’s exclusivity has real costs, both for the industry and for society. The lack of diversity stagnates the healthy social evolution of our societies. With social media becoming prevalent, we see luxury and fashion brands being called out for their behavior. In the past year alone, Gucci and Prada had to pull products off the shelves because they resembled blackface, and Dolce & Gabbana suffered losses worldwide, when their series of ads belittled Chinese and Asian consumers with misfired jokes (Stefano Gabbana’s insensitive comments added fuel to the fire). Product recalls, loss of sales, social division…the cost is real.

It has been proven however, that when companies do their due diligence, inclusivity and awareness lead to a significant return on investment. According to the Boston Consulting Group (BCG), companies with above-average diversity in management produce “innovation revenue” that is 19 percentage points higher than that of companies with below-average leadership diversity.

I believe that it is our moral obligation to learn about this lack of diversity in the industry’s history, and to recognize that we still have a long way to go. Not for the sake of increased profits, but for humanity. I wish I was able to add more images depicting the diverse racial and cultural heritage of fashion, and that more talented entrepreneurs had been allowed to flourish deservedly.

And it goes beyond the history of fashion designers. The sidelining of minorities in the fashion industry is most evidently depicted in how the media and the companies advertising beauty and lifestyle products select their targeted demographic. Luckily, the past years have seen an increase, for example, in the promotion of makeup products for different skin tones.

This past year, with its pandemic and BLM movement, has brought the appreciation-of-diversity conversation to the forefront. I believe that this is a healthy conversation to be having. The more we talk, the more we are pushed towards accountability and acknowledgement of our biases. The more society can move in a positive direction.

During last year’s protests, I asked myself what I could do as an individual, on a small-scale level, to make a difference. My decision was to offer my consultancy services to anyone from a disadvantaged background. Each of us can find a way to contribute to the greater good. We have to leave a better future for our children, a future that is inclusive and that provides opportunities for all. So that when designers like Ann Lowe create a dress, they can put their name on the tag, and they don’t have to work 10 times more to earn the same as their accepted counterparts.